Threads of Tradition: The Ancient Roots of Labia Elongation Across African Landscapes

Page 1 of 2

In the soft hush of a Rwandan dawn, where mist clings to the rolling hills like a whispered secret, a girl named Amina stirs awake. She is young, her limbs still carrying the languid grace of childhood, but today marks a quiet turning point. Her aunt, a woman whose hands bear the calluses of fields and hearths, leads her to the edge of the family compound.

There, under the broad leaves of a banana tree, the lesson begins—not with words alone, but with touch. Gentle fingers guide Amina's own to the delicate folds of her body, teaching her the rhythmic pull that has echoed through generations. "This is for you," her aunt murmurs, her voice steady as the earth beneath them. "For the woman you will become, for the pleasures that await in the arms of a husband, for the harmony of body and spirit." Amina nods, her hands tentative at first, then surer, as the ancient rhythm takes hold. This is *gukuna imishino*, the pulling of the labia minora, a practice as old as the hills themselves, woven into the fabric of life in this corner of East Africa.

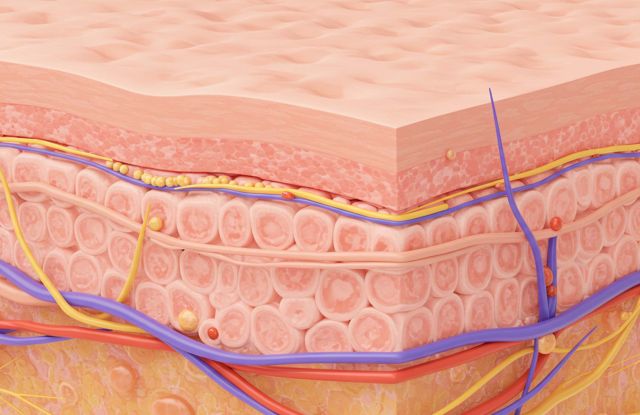

To understand such a ritual is to step back into the vast, sun-baked expanse of the continent's history, where bodies were not just vessels for survival but canvases for cultural expression. Labia elongation, the deliberate lengthening of the inner labia through patient manual manipulation, emerges from traditions that predate written records, rooted in the communal wisdom of African societies. It is a story of women shaping themselves—not in isolation, but as part of a shared legacy, where the intimate meets the communal, and personal adornment intersects with collective identity. Far from a uniform practice, it varies across regions, from the arid plains of southern Africa to the lush highlands of the east, each community imprinting its own nuances on this enduring custom.

The earliest whispers of this tradition surface in the encounters between European explorers and the indigenous peoples of southern Africa. In the 17th century, Dutch settlers at the Cape of Good Hope documented what they called the "Hottentot apron" among the Khoikhoi women—elongated labia minora that hung prominently, a feature that both fascinated and bewildered outsiders. These accounts, often laced with the biases of colonial gaze, described lengths reaching up to four inches, attributing them sometimes to nature, sometimes to artifice.

But anthropologists later pieced together a clearer picture: among the Khoisan peoples, including the Nama, this elongation was no accident of birth but a cultivated trait, begun in girlhood under the guidance of elders. Isaac Schapera, in his 1930 ethnographic study *The Khoisan Peoples of South Africa*, detailed how Nama girls, starting very young, and would be taught by an aunt or grandmother to stretch the tissue daily, using simple pulls with fingers or even wooden tools wrapped in softened bark. The process, spanning years, aimed not for exaggeration but for balance—aesthetic symmetry that mirrored the harmony sought in beadwork or scarification elsewhere on the body.

Schapera's work built on even older observations. Captain James Cook, anchoring in Cape Town in 1771, recorded measurements of labia from 1.3 to 10.2 centimeters among Khoikhoi women, noting how the practice was "universal" in certain clans. These weren't idle notations; they hinted at a custom so ingrained that it defined beauty standards, much like the neck rings of the Kayan women in Southeast Asia or the lip plates of the Mursi in Ethiopia. For the Khoisan, whose hunter-gatherer lives revolved around the rhythms of the Kalahari, such modifications spoke to resilience and allure.

Elongated labia were said to enhance grip during intercourse, heightening sensation for both partners—a practical poetry in a world where pleasure was as vital as provisioning the hearth. Men in these communities valued the trait as a mark of maturity and desirability, while women passed it down as a rite of readiness for marriage, ensuring their daughters entered womanhood equipped for the intimacies of union.

As one traces the threads northward and eastward, the practice blooms into fuller expression among Bantu-speaking groups. In the 1930s, British anthropologist Monica Wilson embedded herself among the Nyakyusa of what is now Tanzania, chronicling how girls there initiated the pulling at puberty, often in secretive sessions by the riverbanks. Wilson's notebooks, filled with the cadence of Nyakyusa songs and proverbs, reveal a worldview where the body was a bridge between the physical and the ancestral.

"The long lips hold the man's seed," one elder told her, invoking beliefs in fertility and retention that tied personal anatomy to communal prosperity. Among the Nyakyusa, the elongation was less about spectacle and more about symbiosis—labia lengthened to cradle and stimulate, fostering deeper connections in the marital bed. This wasn't mere folklore; it aligned with broader African cosmologies, where sexuality was celebrated as a force of creation, not shrouded in shame.

Regional Variations in Labia Elongation Practices

| Region/People | Starting Age | Methods | Cultural Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Khoisan (Southern Africa) | Girlhood | Manual pulling, wooden tools with bark | Beauty, maturity, enhanced sensation |

| Nyakyusa (Tanzania) | Puberty | Riverbank sessions, manual manipulation | Fertility, marital symbiosis |

| Rwanda (Bantu) | Girlhood | Daily pulling with herbal pastes (e.g., Bidens pilosa) | Pleasure in kunyaza, readiness for marriage |

| Zambia/Malawi | Girlhood | Nighttime pulling, herbal aids | Marital harmony, enhanced grip |

By the mid-20th century, as independence movements stirred across the continent, ethnographers turned their lenses to Rwanda and neighboring lands, uncovering parallels that suggested diffusion over centuries. In Rwanda, *gukuna imishino*—literally "to lengthen the ears of the vagina"—traces its lineage to pre-colonial kingdoms, where court poets wove verses praising women's forms as landscapes of grace. Girls, typically in their teens, learn from maternal kin, pulling for 15 to 20 minutes daily over months or years.

Herbal pastes from plants like the *Bidens pilosa* (blackjack) or aloe soothe the skin, preventing tears and infusing the ritual with the earth's own medicines. The goal? Labia extending three to seven centimeters, ideal for the Rwandan art of *kunyaza*, a foreplay technique of rhythmic vulvar stimulation that prioritizes female climax and even ejaculation, often called *kunyara* or "to make rain." Here, the practice flips Western assumptions: it's women-led, designed for their ecstasy, with men as appreciative participants rather than dictators.

Did You Know?

In some African societies, elongated labia were historically misnamed the "Hottentot apron" by colonial observers, distorting a cultural norm into a symbol of exoticism.