Threads of Tradition: The Ancient Roots of Labia Elongation Across African Landscapes

Page 2 of 2

This emphasis on mutual delight echoes in Zambia, where the custom hides behind veils of taboo yet thrives in rural villages. Zambian women, pulling from girlhood under the cover of nightfall, view elongated labia as a secret weapon in love—a silken enhancement that "traps" pleasure, as one anonymous interviewee confided to researchers in a 2015 study. In Malawi and Zimbabwe, similar stories unfold: among the Chewa, it's tied to initiation ceremonies where girls emerge from seclusion with bodies remade, ready for life's dual roles as nurturers and lovers. These aren't isolated pockets; linguistic echoes—like the Swahili *kuchuna* (to pull)—hint at Bantu migrations carrying the knowledge from the Congo Basin southward over a millennium ago.

Yet history rarely unfolds in straight lines. Colonialism cast long shadows, branding these traditions as primitive curiosities. The infamous case of Sarah Baartman, the "Hottentot Venus," paraded in 19th-century Europe for her elongated labia, turned a cultural norm into a symbol of exotic otherness, fueling pseudoscientific racism. Baartman's dissected remains, displayed in a Paris museum until 1974, underscored how external judgments could distort intimate practices. Post-independence, as nations grappled with modernity, the custom faced new scrutiny.

In Uganda, a 2020 clash between the gender minister and traditionalists highlighted the tension: officials labeled it a form of mutilation, while elders defended it as heritage, essential for marital harmony. Surveys show uptake persists—up to 30% of women in some Rwandan districts—often in diaspora communities, from London flats to Johannesburg townships, where grandmothers teach quietly amid the hum of urban life.

"The long lips hold the man's seed," an elder told anthropologist Monica Wilson, reflecting beliefs in fertility and connection that tie anatomy to communal prosperity.

To walk these paths is to confront the universality of body modification. Just as Japanese women bound feet in lotus shoes for elegance or Maori men etched ta moko across faces for status, African women elongated labia as an act of agency within their worlds. It was never about diminishment but amplification—extending not just tissue, but the reach of sensation and connection. In a Zulu proverb, "The river flows from the source," reminding that such customs spring from deep wells of necessity: in societies where marriage sealed alliances and children ensured lineage, a woman's body became a map of preparedness.

Consider Elias, a Zambian farmer in his fifties, sharing stories over millet beer in a Lusaka market. "My wife," he says with a grin that creases his weathered face, "her pulling was the first gift she gave me—not gold or cloth, but the warmth of knowing we fit like hand in glove." His words capture the relational heart of it: for men, it's allure and compatibility; for women, confidence and control. Researchers note psychological layers too—young women who embrace the practice report higher body satisfaction, viewing their forms as tailored instruments of joy rather than generic templates.

Today, as global conversations swirl around consent and health, the tradition adapts without apology. Clinics in Kigali offer guided sessions with medical oversight, blending old ways with new safeguards against infection or asymmetry. Online forums, connect practitioners across borders, sharing tips on sustainable herbs or the emotional hurdles of starting late. It's a living archive, resilient against erasure.

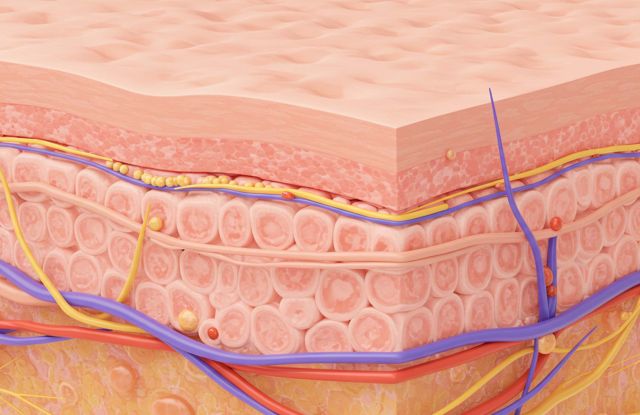

Back in that Rwandan village, Amina grows into womanhood, her hands now expert in the pull. On her wedding day, as drums thrum and guests feast on roasted goat, she steals a moment with her husband, whispering of the traditions that bind them. In her elongated labia, she carries not just her aunt's touch, but the echoes of Khoisan wanderers, Nyakyusa poets, and countless unnamed women who shaped themselves against the horizon. This is the quiet power of origins: not a relic dusted off for display, but a current running beneath the skin, linking past intimacies to future ones. In Africa's vast narrative, labia elongation stands as a testament to how deeply we inscribe our stories on the body—patient, personal, and profoundly human.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the historical origin of labia elongation?

It traces back to pre-colonial African societies, with early records from 17th-century European explorers noting it among Khoisan peoples in southern Africa.

Is labia elongation still practiced today?

Yes, it persists in rural and diaspora communities across Africa, often adapted with modern health safeguards to ensure safety. Its popularity is also growing in other countries as women, exposed to the practice through migration or cultural exchange, adopt it, in their home countries.

How does it differ from female genital mutilation?

Unlike female genital mutilation (FGM), which often involves forced cutting or removal of tissue, labia elongation is a cultural practice involving gradual, voluntary manual stretching without tissue removal. Taught as a rite of passage by female elders, it is embraced by many practitioners as a consensual act of self-expression and enhancement, rooted in tradition rather than harm.

What cultural roles does it play?

It symbolizes maturity, enhances sexual pleasure for both partners, and fosters marital harmony in traditions like Rwanda's kunyaza.

Has colonialism affected perceptions of this practice?

Yes, colonial accounts often exoticized or pathologized it, as seen in the tragic story of Sarah Baartman, influencing modern views.